Since June 2011, I’ve been working on Storyvoid, and Instapaper client for Windows. With 619 commits spanning nine years of active development, it’s a labour of love. As a free app, it isn’t going to be a business or a breakout hit, but it is mine, for all its warts.

There are technical design choices I made during Storyvoid’s development that were reasonable given the context, but today seem odd or out of vogue.

How it started

Windows 8 was under active development and I was working on Xbox Music & Video (Later, Groove Music / Movies & TV). Throughout my day, I would come across bookmarks that I wanted to save & read later. I was using Windows 8 as my day-to-day operating system (Gotta eat your own dog food, right?), so I needed a solution that would work there. Sure, there was the official Chrome extension from Instapaper but Internet Explorer didn’t support extensions. Windows had added the fancy new Share Charm, letting me share from everywhere in the operating system! As many a software developer does, I thought:

I’m a capable programmer, and I work on this stuff everyday. I can probably make a share target real easy!

And off I went to quickly whip up an app to act as a share target.

Of course, it’s never that easy.

Walkthrough

Block diagram

Building the basics

Sharing a link using the Instapaper API shouldn’t be that hard, right? Theres a nice /api/v1/bookmarks/add endpoint that takes a URL! Well…

- I would like a full app one day — so I can read on my fancy tablet

- I should probably use the full API, not the “Simple Add-only” API

- Oh, hey, look I need to auth

- Oh… ohh, what is this ‘Signed OAuth Requests’ thing?

I decided to use the Windows Web App stack:

- It’s what I used in my day job, and would let me experiment with work-relevant choices

- Working inside Microsoft gave me an indication that at the time it was the One True Platform™ for Windows 8 applications1

Building OAuth 1.0 request signing (aka xauth)

To use the full Instapaper API you need to follow the request signing flow for OAuth 1.0a. It’s not a full OAuth flow; there’s no browser redirect dance to obtain the tokens. It’s basically the Twitter xauth pattern. But it does require the signing of the request payload et al.

This required diving into both the specifics of OAuth signing itself (Which parts of the payload participate in signing, how those contents are encoded, which algorithm, how entropy is sourced), and mapping that into an at-the-time young platform’s cryptographic functions. JavaScript didn’t have implementations of the required cryptographic libraries – certainly not in the MSHTML runtime environment of WWAs.

Windows did have those APIs and they were projected into the WWA runtime environment (but not the standard browser environment). This allowed me to use Windows.Security.Cryptography APIs to perform the computations to sign requests to interact with Instapaper.

Of note:

- Browser built in encodings don’t conform to the requirements of OAuth, which needs RFC3986 encoding.

encodeURIComponentdoesn’t fully comply, so you need some extra transforms - Writing tests for this required building a minimal twitter client that would post, and then retrieve the data from the timeline to ensure it was correctly posted

This resulted in a nice, self contained library that could be leveraged to wrap the Instapaper service API.

Instapaper API

Wrapping Instapaper’s API was a straightforward task of projecting friendly objects, and exposing errors to the consumers of the API in a consistent way.

One area that proved frustrating – and would later escalate to annoyance – was the service limits on the number of bookmark additions to 120 per day. A day being bounded by midnight on the US east coast, not a rolling 24hr window.

This is not really documented, and required me to stumble upon it during particularly active implementation sessions. This led to adding tracking in my app to help understand if I was getting close to the limit when running unit tests repeatedly. With this limit in mind, I ended up with some unit test gymnastics aimed at minimising the number of bookmark additions that were performed, so I could have more unit test iterations as I wrapped more of the Instapaper API. At the time, I was using two different devices to develop, so chose to roam the settings — don’t need to be confused on my second device when tests randomly start failing.

This wrapper is basically a simple transformation on data into & out of the endpoints in JavaScript. Nothing super interesting here.

Database API

The app needed to store the data offline, and a database seemed logical. At the time there were really only two choices:

- JET Blue database (Extensible Storage Engine)

- IndexedDB

JET Blue wasn’t directly exposed into the WWA runtime environment, so would require writing a C++ wrapper, and all the baggage that came with that. IndexedDB was a callback API (Native promise support in the browser had yet to arrive), which wasn’t pretty, but at least it was battle-tested.

At the time, I was attempting to really embrace Open Source & avoid Not Invented Here™ syndrome, so found db.js which provided more holistic API around IndexedDB, but continued to expose a callback style API, while hiding some of the details of attaching event handlers for each request.

As I’d already chosen to use WinJS as my “Framework” (Almost required on WWA at the time), it made sense to leverage the robust Promises/A implementation in WinJS to project a promise API from db.js.

Given it was going to depend on WinJS, I forked it, and made some additional quality-of-life changes:

- Ported the tests from Jasmine to QUnit

- Added a wrapper application to run the tests on Windows

- Added a

Signalclass to make working with promises a little easier - Added the Promise API

The initial diff can be seen here.

Better Templating + View/View Model Separation

WinJS had a simplistic control model (e.g., a way to encapsulate compositions of other controls). The model was primarily imperative, causing consumers to build their UI procedurally. For the HTML world, this didn’t feel like a great model – it’s implicitly declarative, after all. WinJS did have a templating capability, but there wasn’t anything that:

- Combined templates with controls into a holistic control model

- Support a proper life cycle for the controls

- Support nested, templated, controls

In my case, I really only wanted 1 & 2 – which led me to create utility functions that gave me those pieces:

- Allow layout to be declared in templates and automatically assign elements to properties on the code behind

- Caching of the templates loaded from document fragments

- A constrained lifecycle for controls, primarily around removal from the DOM tree

This was prior to react (by ~2 years), and the <template> element in browsers.

Building app logic

It was now possible to start building the largest component – app logic. I had a concrete database for storing Instapaper data, but the app needed the ability to sync local changes to the service, and discover changes on the service to apply locally.

I’d clearly wandered far from my ‘Lets just save bookmarks’ path, and stumbled into a full application (It’s a passion project; I can stumble around if I want!). Saving me significant analysis paralysis was the implicit model that Instapaper had through it’s “have” model, defining the basics for how sync could be implemented.

Instapaper “have” model

Instapaper has a single master in it’s sync system: the service. But it also assumes there are multiple clients making edits (iPhones, iPads, and the Browser for the official clients), so it has to resolve something more intentionally than ‘last write wins’.

Specifically, Instapaper has two properties that determine which read progress is applicable:

- Timestamp

- Opaque service computed hash

These are attributes of the bookmarks in the service, and are used when asking for the contents of a folder – caller provides a list of bookmarks + progress + hashes, and they’re compared to what the service service has. The returned data is a set of adds/removes/updates for a given folder – allowing a client to assume those return values are ground truth. This only applies to the contents of a folder, and even then it only applies to presence in the folder, and the read progress. Other properties that are mutable – such as “like” status – aren’t part of this calculation, and folders list has no ‘what changed, are there new folders?’ behaviour.

Creating a change log

To capture all offline changes and then at some future point reconcile those changes, I needed a change log. Initially I considered just making local changes to the database, and then requesting folder-by-folder on the service, matching state. This presented a few challenges:

- Deletes would still have to be tracked discretely: Instapaper has a limit on the bookmarks returned, vs what is actually in a folder. Just because it’s missing in the remote folder contents does not mean it was deleted

- Folder creation required explicit tracking

- The optimised path of ‘have’ behaviour was designed to reduce the cost of a request where nothing changed. ‘have’ does not account for liked state being changed

While handling a ledger of deletes isn’t complicated, the latency of requesting all folder contents would be detrimental to the sync experience. Coupled with tracking the other items (folders, likes) explicitly, it seems that we’re half way to doing the full version anyway. So… here I go capturing of mutations made to the database.

Two notable additional decisions fell out of this:

- Progress changes are not captured as discrete changes. They’re just applied to the database – they’ll be round tripped with the ‘have’ process during a sync

- All changes are made directly to the database, and only transit to the service through the sync process 2

Change storage

Two tables capture the changes – one each for bookmarks and folders. All types of changes were captured in each of these tables. Because IndexedDB is a document database, theres no strongly typed schema enforced on records. Each edit was given a type (Add, Delete, Move et al), and they were maintained in the order they were inserted into the database.

The polymorphic + relative ordering nature was an intentional design decision that felt easy at the time:

- Simple ordering of different operations relative to other edits

- Easy to loop over and handle each operation.

The reality was that relative ordering between operation types wasn’t needed, just within a specific change type.

Capturing changes

Capturing a single, atomic, change was easy – simply write the change information to the updates tables, and you’re good. However, when viewed in context, this no longer was all that was needed. What if:

- They’d liked a bookmark, and now deleted it before the sync?

- They’d deleted a folder, only to recreate a folder with the same name 3

- Moved a folder from folder A to folder B to folder C (Only one of these really matters)

- Archived (effectively a folder move, but not quite), and then unarchived

These meant that to correctly capture the target state the user might have been aiming for, I would have to ensure that we reconcile any previous updates for that same artefact. This required reading existing state, and recomputing the ultimate end result operation to be written to the database.

While JavaScript is single threaded, the IndexedDB interface is non-blocking callback based, and because the message pump in the browser was allowed to, well, pump, while handling database operations, this did open a possible issue where concurrent operations would come in while sorting out the set of pending operations.

Ultimately, I decided not to worry about that. This was a very small window of possibility, which with careful consideration of the (future) UI it would be narrowed further. YOLO, as kids say these days.

With this in mind I made the choice to just place this processing in the DB models mutation methods, and have it all bundled up as a small monolithic thing. You get a database and you get some pending changes. 4

Syncing the changes

I’ve got a mechanism capturing changes — the change log — and some implicit constraints on how to sync (the ‘have’ model). I just need to do something with those components to perform the actual sync.

Getting the order right

The initial expectation was that we’d use the entity-type (e.g., folders & bookmarks) scoped relative order of changes not covered by ‘have’ to replay the local changes against the service before syncing the folder contents using ‘have’.

Digging into this, it became clear this wasn’t going to be so easy to apply. We might have out-of-order moves, multiple moves, or other changes that relied to heavily on strict ordering for things to go just right.

The top-level ordering was folders first, followed bookmarks. Within each of these, sub operations were intentionally ordered too.

Folders

- Sync Adds & Deletes (in any order) 5

- List remote & local folders

- Compare the two lists, and apply adds or removes as appropriate

After completing these operations the folder entries match, but the contents still need to be sync.

Of note, when a folder deletion is sourced from the service the contained bookmarks are orphaned locally — they’re not deleted in the database and aren’t returned in any user-visible UI. This is because the contents — the downloaded bookmark body & images — may have simply been moved to another folder. We don’t want to pay the cost of re-downloading the bookmark contents if we can. If it’s truly been orphaned, it will be cleaned up when the bookmark sync process completes in a garbage-collect like sweep.

Bookmarks

Syncing bookmarks happens folder-by-folder, barring adds, likes, and deletes, which are folder agnostic. There is support for controlling the folder order, which is influenced by the current folder being viewed in the UI – that’ll be synced first, and then Unread, Archive, and all other folders in an undefined order.

- Locally added bookmarks

- Folder by Folder changes

- Sync the folder itself if it’s a ‘new’ folder 6

- The ‘have’ contents to update progress remotely and locally, service-removed & added bookmarks in this folder

- Local Like Status changes are applied (i.e., unliked ➡️ liked, and liked ➡️ unliked)

- Sync the Like folder like a folder 7

- Sync bookmark deletes

- Clean up bookmarks not in a folder

Following this process gets a reliable set of local changes up that matter (not all local changes are critical), while relying on the service to be the ultimate source of truth.

These processes tend to be quick, bounded by service service performance. Gathering up local changes from the database is a fast process, especially given how many devices have flash storage today.

Bookmark download

Again, on the surface, bookmark download looks easy – Instapaper provides a nice get_text endpoint that returns the bookmark body. Write it to disk, and you’re off to the races?

Not so much. There are a few peccadilloes between that and rendering the document – and they impact the download phase. Specifically:

- Bootstrap script injection

- Body manipulation

- Image download & extension deduction

- Thumbnail image selection

Bootstrap script injection + body manipulation

When a bookmark is viewed, there are certain interactions users expect – typeface choice (size, family), layout, and command interactions (like, delete, move etc). With the capabilities available in an x-ms-webview (think iframe with narrower security profile), there needed to be script running within that web view. However, you can’t arbitrarily inject script to the document externally – you need a component within the web view to handle the messages, and process them. There is also no capability to easily process the byte stream as it’s being loaded by the web view, which would enable an unmodified bookmark body to be persisted to disk.

I decided to inject script into the head of the HTML bookmark body when downloading the body. With this script injected, I could bootstrap upon loading, allowing all other manipulations to happen at runtime. This was to minimise the reprocessing of downloading documents to handle functionality changes.

Additionally, not all bookmark bodies are created equal – some bodies don’t have a wrapper element around the body elements direct children. This leads to challenges with controlling the margins in the document, as well as how runtime elements are injected. So, to mitigate this the children of body are re-parented into a container div.

Some small house keeping items also happen in this phase:

DOCTYPEpreamble is added, to make the bookmarks real modern HTML documents (E.g., don’t want quirks mode)- 400 characters of document text (e.g., excluding markup) are extracted, and placed in the database to serve as an article preview

Because these manipulations happen during bookmark download, and it’s a one-time operation per bookmark, there is the risk (over the long term) that any changes to this on-disk data might trigger a mass re-download of bookmarks. This could result in a significant time sink performing migrations depending on the number of bookmarks that are in a users account.

Image download & extension deduction

A key promise of a full-fledged offline Instapaper application is that when viewing the bookmark offline you’ll see all the images from the article (e.g., diagrams, photos referenced by the bookmarks). If you render the downloaded bookmark body while online, everything is hunky-dory – images load! This is because the Instapaper pre-processed the image URLs to be fully qualified URLs (scheme + host + path, https://example.com/image.jpg). If you viewed the bookmark while online once, images would be cached in the apps implicit browser cache and you’d be OK ‘cause those images would be serviced by the browsers cache.

But that is not how a user reads bookmarks – they’ll sync their app, and read at a later date for the first time. This means we have to download referenced images, and rewrite the URLs in the bookmark body to reference the local file path. This is pretty simple act of issuing a GET request to the URL, persisting to the apps managed cache, and rewrite the URL to be relative (e.g., sourcing from the local file system). For YouTube & Vimeo videos, special logic calls those services for a thumbnail image. This method also helps mitigate any automatic browser cache purging that happens over time to reclaim system storage.

However, it’s not entirely that simple…

Everybody lies – House, M.D.

During early testing, it became clear that not all images file extensions in their URL, nor are they accurate if present. Most browsers will do sniffing to detect the image type before rendering. However, in the x-ms-webview case, that wasn’t always successful, resulting in broken images. Additionally, when viewing the files downloaded by the app (should they go digging), seeing the extension gives the user peace of mind as to what has been downloaded. Of note, it also simplified thumbnail selection (discussed later).

However, in the limited scope of the WWA environment, and in the process of downloading, we needed to detect what the actual image type was without rendering/decoding the image (security first, performance second):

- Read the request response stream into memory

- Inspect the first 8 bytes, comparing to known headers for PNG, JPG, & GIF formats.

- If theres a match, use the detected extension

- If no match, use the mime type returned from the image request

- Still not match, don’t give the file an extension, hope the browser can sort it out

Thumbnail selection

The visual presentation of a bookmark in a list involves a hint to the contents. For bookmarks that only contain text, the first 400 characters are extracted. If there is at least one image, an image is used. As with everything, there are exceptions:

- Don’t select animated gifs; they’re distracting!

- Don’t select images below a certain size, they’ll look blurry rendered in a list

- Don’t select images that weren’t successfully downloaded

When selecting the thumbnail, I pick the first one that doesn’t match these criteria, and persist the path to the image in database.

UI

At the time, MVVM (Model/View/View Model) was the de factor paradigm for multi-layered UI. However, over time MVVM (and MVC et al) had a tendency to break the rule-of-thumb that lower layers are not explicitly aware of the layers above. The idea being that if your lower layers are agnostic, you get looser coupling, and better maintainability (e.g., non-UI component isn’t reaching into UI component, creating tight circular dependencies.).

In a previous project (Microsoft Test Manager), I’d mitigated this by separating the UI into a different compile unit from the models. The ‘View Model’ would declare what class implemented the UI for that component (through stringly typed attributes). I decided to replicate this in Storyvoid, by creating something I termed “Experiences”. The idea being that a type would expose an experience property that contained a map of experience type identifier to implementation type name. This would allow View Models to model the different states by pushing new view models onto a stack, and then this component would transparently create the UI that was required.

In the end, only one ‘host’ was created – WwaExperienceHost. In the grand scheme of the project, I don’t think it brought a huge amount of value. I still like the pattern, but only for applications with a greater diversity of experience – Storyvoid only has 3 primary views, and one of those (Sign in) is only seen once in a typical users journey.

Signed in experience

The signed in experience is primary experience of the application. People may spend more minutes in the reading view, this bookmark list is where users land on app startup, and has the most complex interactions. This experience accrued a large amount of functionality that at times can feel a little like a kitchen sink – but if one digs in a little, it’s clear it’s not. There are a couple of pieces that would likely be better placed else where, but it was ultimately simpler to attach them to the signed in experience. Primary components:

The signed in experience is primary experience of the application. People may spend more minutes in the reading view, this bookmark list is where users land on app startup, and has the most complex interactions. This experience accrued a large amount of functionality that at times can feel a little like a kitchen sink – but if one digs in a little, it’s clear it’s not. There are a couple of pieces that would likely be better placed else where, but it was ultimately simpler to attach them to the signed in experience. Primary components:

- Display bookmarks in the selected folder

- Display of the folder list

- Sort options

- Item Commands

List display

Displaying a list of bookmarks is a simple affair – get a sorted list from the database, and display them. However, there were two aspects of the design that added some additional work:

- Heterogenous item display: Image tiles and text tiles

- Applying database changes to items that are displayed, sort aware

The WinJS.UI.ListView class provides an itemTemplate property to leverage WinJS’s templating engine. This is only one template – if you wish to have varying item look & feel, you’d need to handle it dynamically in the layout. It is, however, possible to provide a render function to this property, which allows you to dynamically select a different template. This is what I did, selecting a different template if the bookmark has an image available for it.

Given the nature of the list being sorted & supporting selection, handling database changes (add, remove, update) without re-rendering the entire list was key. Thankfully, WinJS also provides ListView.createSorted, a simple wrapper that projects a sorted view over the underlying collection, maintaining the sort when items are added / removed / updated.

Commanding

For a given bookmark, there are a number of operations that can be performed:

- Open in the app

- Open in the system browser

- Download the article contents

- Like / Unlike

- Delete

- Move

- Archive

Some of these (like toggle, archive) are dependent on article state, the folder being viewed etc. Others (opening, downloading) depend on how many are selected e.g. you can only open one article.

These commands are also displayed on multiple surfaces (toolbar, context menu), as well as supporting keyboard shortcuts. One doesn’t want to manage these as discrete locations; nor does one want multiple implementations of those operations.

Many platforms, including WinJS, provide a framework-wide command pattern implementation, enabling that decoupling. The implementation in Storyvoid isn’t discrete objects implementing the commanding interface – instead, they’re wrappers around member methods on the signed in experience. While not perfect, this does help contain the scope, and limit the proliferation of many single-use classes to implement those operations. Of note, these are all implemented on the view model, and only offered as list of commands to the view itself – maintaining that strict policy of never being aware of whats above you in the stack.

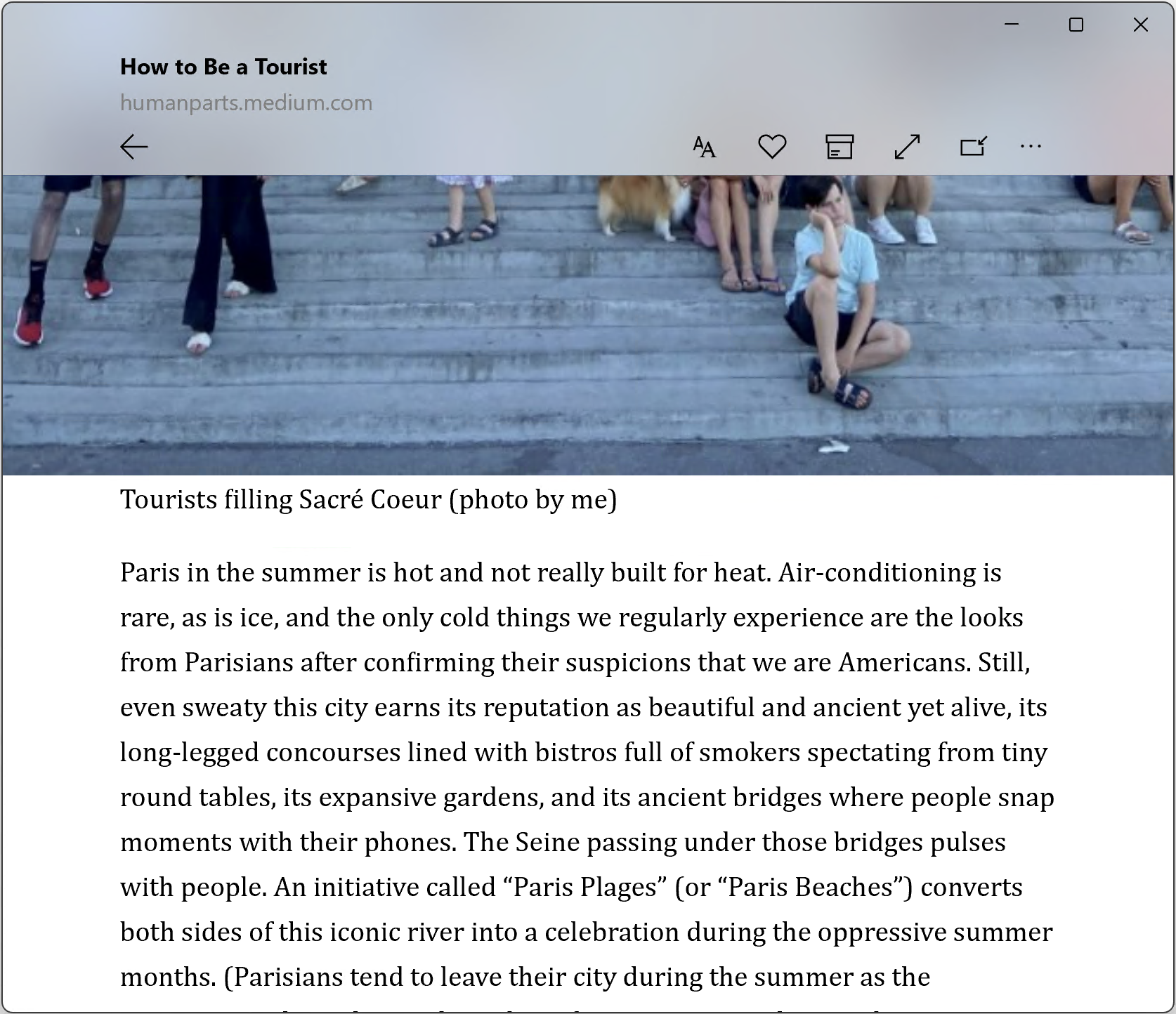

Reading view

The most critical part of the application (it’s a reading app after all) – it must be quick, compelling, and reliable. The implementation of this experience follows the MVVM-ish model as the rest of the application, but has some significant quirks that are a byproduct of security. The primary mechanism for loading the article is within a security restricted

The most critical part of the application (it’s a reading app after all) – it must be quick, compelling, and reliable. The implementation of this experience follows the MVVM-ish model as the rest of the application, but has some significant quirks that are a byproduct of security. The primary mechanism for loading the article is within a security restricted x-ms-webview, preventing direct manipulation of the contained document. Coupled with the earlier choice to only inject bootstrap script tags, the significant document manipulation needed some complex scaffolding to make it simpler to implement.

Message passing

There’s really two parts here – ‘windows had a bug’, and an ergonomic API for async calls across the message pipe. In hindsight, the generic nature of this component may have been over engineering. It did simplify the cases where two-way message passing was required.

Bug

Normally, within a web view environment, you can invoke window.external.notify to raise a message + payload to the hosting environment. However, in Windows 10 (10.0.10240), x-ms-webview’s pointed at a ms-appdata://-schemed URLs could not call this API. This meant that while you could pass a string back synchronously, any async work or web view initiated operations were not possible.

However, it was still possible for the host to inject their own objects using addWebAllowedObject. Using this API, I created an object that mimicked the window.external.notify pattern, and injected it as MessageBridge. Ultimately, the class itself is very simple – one method, and one event.

Message Passing

No matter the specific pipe that the messages are sent through, the API for that pipe is a simple message type + payload. There is the invokeScriptAsync, which lets you pass stringly typed values back. But if you have an asynchronous operation (e.g., adding a script file), it required a specific ‘response’ message. Handling this on an operation-by-operation method was going to be repetitive at best, so I added a WebViewMessenger class to wrap those asynchronous calls with Promise API.

It works by:

- Generating a unique response ID

- Crafting a payload that includes the message ID, message payload, and the response ID

- Submitting that through

invokeScriptAsync

The receiving component within the web view turns this into a dispatch, supplying the payload and a completion handler callback that hides the details from the handler.

This results in a simple API where someone can call an interface similar to await addScript("foo.js"), knowing that upon the promise completing, the script is complete.

The in-app usage of this pattern ended up being limited, but for the four use cases that came up it made them much simpler.

Commanding & shortcuts

Because of the hosted nature of the reading experience, the commanding pattern paid off in dividends. The only place with access to the database was the main app – it was impossible for it to execute operations on the database from within the web view.

There is also the way web views (and iframes) handle focus. If the focus is within the web view the host doesn’t see those keyboard interactions, nor does it see mouse clicks / touch interactions i.e., they don’t bubble outside of the web view. This means that we have to handle them within the web view, forwarding appropriate operations to the host to perform the actions on its behalf.

For keyboard operations this is relatively simple — one can capture a large subset of operations generically, and just forward all keyboard input to the host. In this, case all Ctrl+{whatever} & function keys were forwarded to the host, where they were matched with commands.

For mouse and touch, there are ‘default’ browser actions (selection, scrolling, tabbing to links, etc) that needed to match expected browser behaviours. A more targeted approach was taken for those commands (e.g., toolbar toggle, link-invocation) of specifically capturing the interaction and forwarding it on to the host. These are also the cases that often didn’t quite fit the command scenario – they were often just UI interaction with no meaningful behaviour behind them.

One aspect here is that the toolbar itself was entirely in the host, but the visually it was layered with the actual reading view, so some complex UI-layer interactions were required to create a compelling experience — scroll/reveal animations, along with resizing to match reader-child content that was opaque to the host.

Visual design

Key to any reading experience is the ability to chose a reading theme, customise the font size, line spacing, and margins of the content. These also need to be persisted across reading & app sessions. Themes were modelled as named-identifiers, with font size, line spacing & margins as explicit values within hard-coded bounds. These were kept in the users local settings store, written the immediately upon the user making a change to them.

These visual tweaks also had to interact with the overall design of the reading experience, which was focused on ‘more text, bigger images’:

- Hiding the toolbar on scroll

- Aesthetically pleasing content blur behind the toolbar when overlaying text

- Full-window-width images when they were large enough

Toolbar

The toolbar was not drawn in the bookmark web view, but in the main app area. This leads to a challenge with the scrollbars. The toolbar was designed to go the full width of the window, and overlay the content using a tasteful blur.

However, to get the correct blur, the toolbar in the right position, and the scrollbars, it required custom scrollbars. Here an external library called OverlayScrollbars was used with some small customisations. This allowed the scrollbars to be placed above the reading content, even when the scrolling content was behind the blur layer. The trade off was there was a small lag on the scrollbar position during a scroll — this is hardly noticeable, and seemed an appropriate tradeoff for the desired aesthetic.

Image sizing

For certain window sizes the design called for images to be drawn full width of the window. However, past a limit the size needed to be constrained to the width of the text. This wasn’t as simple as width: 100vw & width: 100%, due to the margins of the text — the margins of the image needed to be negative for it to extend beyond the bounds of the text container column.

This is done by monitoring for the size of the web view changing, and re-applying explicit width or margin dependent on the size.

Titlebar

As mentioned, the titlebar was an area that required customisations. It’s important to call out that for WWAs, this isn’t intrinsically supported — while the colours could be configured through a standard API, the API for extending the app drawing area was explicitly hidden from WWAs.

However, they’re merely hidden from the JavaScript runtime, not blocked from being executed within a WWA process; just not called directly from JavaScript. With the help of a custom C++ class, it was possible to re-project that API to the JavaScript environment to support that capability. The downside was it wasn’t possible for us to re-define the draggable area — I didn’t really want to do that, so wasn’t a problem.

With this class it’s now possible to switch between default title bar in the bookmark list and a custom one where the article content is full bleed while reading.

Telemetry

Part of any good application is being able to monitor it in production e.g., which parts of the application are being used, what errors occur, or how much data is in the app. Given WWAs slightly odd overlap of web technology in an offline-scenario, there were very few telemetry libraries that fit the bill.

I ended up creating a C++ library to store-and-forward telemetry datapoints to Mixpanel – you can read more about that in another article.

In production

This application has been in production for ~4 years at the time of writing. It has an astonishing 7 daily users (albeit steady at that value). The most significant issue seen in production was a timezone related issue in the telemetry library.

It’s survived multiple windows releases without any issues. As the windows platform evolved, it’s become clear that applications need to be written in the native UI stack – XAML. I’m in the middle of a long rewrite of the application to C# – hopefully it won’t take as along as the first release. (🔮 says: Outlook not so good)

This choice is dripping in internal politics, and it would eventually shift over the next three years to being the other way. Continuing to work on a WWA in my spare time gave me unique insight into the way the WWA platform was deprioritised and allowed to atrophy. ↩

Two exclusions: Read progress from the reading view when the viewer is closed, and additions from the share charm; those are directly applied to the service. In the case of read progress, they’re also applied to the database ↩

Instapaper uses the title as a proxy primary key, so depending on later sync decisions, that would be problematic ↩

This did lead to some wonkiness when applying service changes, with flags being passed in to say ‘No, this came from the service, don’t write pending changes. With the rewrite to C#, I handled this differently by exposing abstract events that could be used to rebuild the same pattern ↩

Deleting a folder moves the contained bookmarks into the unread (i.e., the default) folder. However, there is a bug in the Instapaper service where it actually just orphans the bookmarks. The API still allows you to move the bookmarks into other folders, so it isn’t lost completely. This is a very annoying bug that even today, we don’t really handle in the client due to the not-to-spec behaviour. ↩

A user might add a folder offline, and move bookmarks into that folder while still offline. We can’t sync a folders contents if the folder doesn’t exist. ↩

The Liked folder isn’t really a folder – it’s a virtual folder made up of liked bookmarks across all folders. However, due to the per-folder sync limits, there is a possibility that liked bookmarks aren’t present within that limit, so won’t be seen during a folder-contents sync, but are returned when listing the liked folder. This means we need to special case sync it’s contents to ensure that progress updates etc. are round tripped to the service. ↩